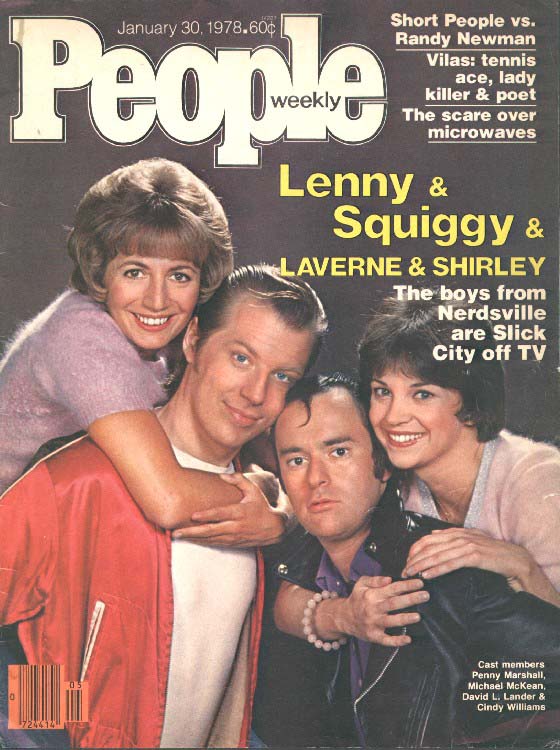

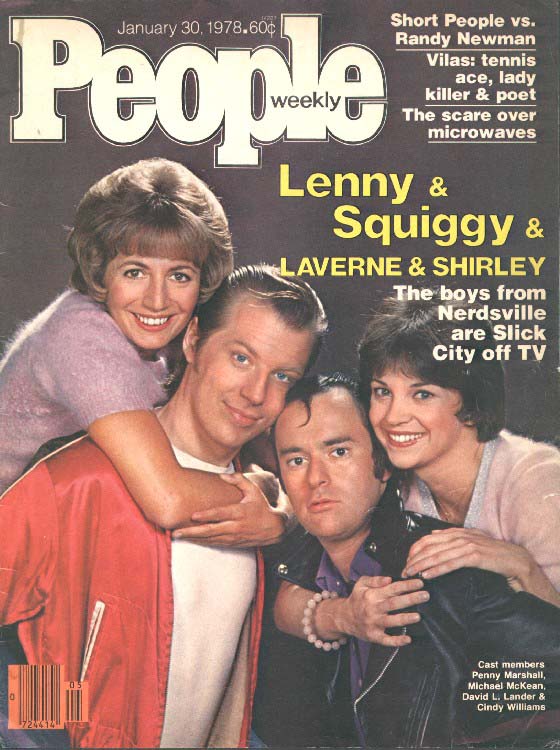

PEOPLE Weekly--January 30, 1978

Admirers with clout never hurt, so when Rob (TV's

"Meathead") Reiner and his wife, Penny Marshall,

invited unemployed actors Michael McKean and David

L. Lander home for a party and commanded "Do 'em,"

the boys were on. "'em" were a couple of

blue-mouthed greaser characters named "Lenny" and

"Ant'ny" that McKean and Lander, both now 30, had

created back in college 12 years earlier.

Fortunately for them, a Happy Days spinoff was in

the works and most of its formative figures were at

the party--not to mention in the family. Penny's

brother was to be co-creator and executive producer,

her dad producer, and she herself was to play a

character called Laverne. Cindy Williams was cast as

costar Shirley, and the McKean-Lander team was hired

as writer consultants. They wrote themselves into

the premier as Lenny and Squiggy (Ant'ny was renamed

Squiggmann to add a Teutonic touch to the otherwise

disproportionately Italian cast). "The show looked

like a disaster at that time," McKean marvels now.

"I had never been involved in a network show before

and didn't know something that seemed to be a mess

could end up an enormous hit."

That's one of the few understatements of TV history.

Those bubble-brained beer bottlers, Laverne and

Shirley, and their even dimmer Shotz Brewery truck

driver neighbors, Lenny and Squiggy, are as of their

second anniversary this week the No. 1 series in TV.

Though they themselves have sometimes been at

loggerheads on the set, Penny and Cindy are in

accord about their second bananas. "I don't know any

better guys to work with," says Marshall. Williams

calls both "terrific actors. That's why they

convince people they're creeps."

Cindy, of course, knows Lander a bit better than

McKean, since "Squiggy" squired her briefly in real

life just after the premier. "We were in love with

eachother for a good two weeks," says Lander. Both

decided that a studio romance was "too messy," he

adds, "not only for us but for the rest of the

cast." Now platonically close, Lander calls Cindy,

who then took up with a sculptor, "one of the

greatest actresses I know." Equally effusive about

Penny, he calls her "very understanding and

sensitive to people's feelings. It breaks my heart

that she doesn't realize how much she's worth as a

person." Lander even goes out of his way to squelch

rumors of dissension over nepotistic Marshall

law--the latest was the hiring of Penny's sister as

associate producer and casting director.

The boys are busy enough protecting their own

characterizations. McKean notes that the original

and "completely obscene" Lenny and Squiggy had been

"considerably toned down for TV--unrecognizably so."

They wondered, says David, "Can we be clean and

continue to be funny?" The Nielsons have decreed

that they can, due largely to the fact that Lander

and McKean constantly rework their scripts. "If we

left it up to the writers," carps McKean, "our

characters would wind up being as bland as Ralph and

Potsie on Happy Days, except with funny voices and

ducktails." Lenny, he says is "a dead ringer for a

guy I knew. But you couldn't laugh to his face

because he'd kill you. He was very strong and very

unprincipled." Likewise, says Lander: "Squiggy is a

combination of people I knew and despised. You have

more freedom playing people you hate. There are

people like them who haven't outgrown their silly

dreams," he says. "Laverne and Shirley are more

intelligent, but they haven't grown up either.

Squiggy looks in the mirror and thinks he's the

handsomest guy in the world. These are the kind of

people who would idolize the Fonz. He's their man."

Lander, who was born David Landau in the Bronx,

would be mistaken for neither. (He changed his name

twice, the second time adding the middle initial, to

avoid conflict with other actors.) "I was born out

of comic relief," he says. "My brother was very

serious and very bright. At four he had memorized

Bach." So high school teachers Stella and Sol Landau

planned a playmate to lighten up his life. "I hope I

cheered him up," says Lander, whose brother, Robert,

is now an opera singer. "If I hadn't, there's no

telling how many kids my parents would have had."

Except for a brief period as a child when, Lander

recalls, he wanted to be "a killer" like on TV, "I

always knew what I was going to do." Michael McKean,

son of Gilbert McKean, one of the founders of Decca

Records, and librarian Ruth, knew too by the time he

was in high school on Long Island's North Shore.

Lander's and McKean's trajectories crossed when they

both arrived at Pittsburgh's Carnegie Tech in 1965

to study acting.

Insomniacs both, they thrashed away nights thinking

up comedic attacks on "tacky showbiz and cornball

comedians," says McKean. They even made up a sitcom

called Widow and Son, about Corky Widow and his pop,

which they performed onstage with a laugh track.

"Talk about history repeating itself before it

happened," exclaims McKean. After a year of cutting

morning classes they were asked "not to come back,"

as McKean delicately puts it. Lander, though, went

on to NYU and crafted one-liners for Walter Winchell

and Earl Wilson before splitting for Hollywood in

'68, where a college friend, Albert Brooks, had put

him in touch with Rob Reiner. The two clicked and

did some TV writing together, and Lander thought,

"Wow, here I am only 19 and writing for television.

But boy did the drought hit fast." Reiner wound up

with the Smothers Brothers, Lander at an answering

service. Starving off boredom with funny voices, he

attracted the attention of a client who had

connections with the Credibility Gap, a radically

satirical radio show.

McKean had meanwhile also himself enrolled in NYU.

He had drifted briefly into drugs ("not to the point

of real danger") and into the late-'60s protest

movement. "I did a lot of hooting during the hoot

period," he says. "I was the guy with the guitar in

the march on Washington." Then he met a girl from

Los Angeles, Susan Russell, whom he followed out to

the coast in 1970 and married later that year. There

he was reunited with Lander, also married by that

time, and joined up with the Credibility Gap. The

show went on the road in '72, and Lander and McKean

went with it. "There was just one giant 'huh' from

the audience," says Lander, who refers to their

itinerary those years as the Bermuda Triangle.

Then came Laverne and Shirley. "When we started we

were all kids," says Lander. "Ratings were like a

foreign language to me." Stardom was also a shocker,

and it undid David's seven-year marriage to

photographer Thea Pool Lander. "That success faced

us with an adjustment we couldn't make," he says.

"Suddenly she became Squiggy's wife, and she's an

independent person and that's why I love her." They

were divorced in '76 and Thea now works in Portland,

but Lander calls her his "closest living relative"

and says, "I love my ex-wife very much. I've seen

her three times in the past three months. I hope and

pray we are friends for the rest of our lives." His

new house in Hollywood makes him worry, he jokes,

whether "this is some kind of commitment. Do I have

to raise this house? But it's modest. If it were a

person, it definitely would not brag."

The more settled McKean has also recently invested

in a home, his in middle-class Studio City, where

after work he likes to "wander around the house in

my bathrobe as kind of a creative outlet." His wife,

Susan, he says "was very considerate about

delivering our son. She went into labor on

Sunday--my day off." Pop beams, "It's the best thing

I've ever done that had a title on it."

McKean and Lander still aren't used to the Tuesday

Night Fever they've helped create. When McKean's

garage mechanic recently refused to accept payment

for a repair, McKean wanted to say, "Why didn't you

do that for me when I was poor?" Lander, even while

he hopes for a Lenny-and-Squiggy spinoff of the

spinoff ("There's so much more to the characters

that we could develop"), is also fuddled by stardom.

When a fan came up to him not so long ago and said,

"Hi, David," he was stunned by someone knowing his

real name. "Do... do I know you from school?"

stammered Squiggy. "No," said the fan. "You're on

TV."